Physical fitness is essential for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. It helps us to stay in shape, reduce the risk of illness, and increase our energy levels. There are 5 components of physical fitness that are essential for overall health and well-being. These components are cardiovascular endurance, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, and body composition. This article will discuss each component and how it contributes to physical fitness.

What Are The 5 Components Of Physical Fitness?

The 5 components of physical fitness are often recognized as:

1. Cardiovascular Endurance: This refers to the ability of the circulatory and respiratory systems to supply oxygen and nutrients to the muscles during sustained physical activity.

2. Muscular Strength: This component measures the amount of force a muscle or group of muscles can exert against resistance.

3. Muscular Endurance: Muscular endurance is the ability of a muscle or group of muscles to perform repeated movements or hold a position for an extended period without fatigue.

4. Flexibility: Flexibility is the range of motion around a joint. It is important for preventing injuries and improving overall mobility.

5. Body Composition: Body composition refers to the proportion of fat and non-fat mass in your body. Achieving and maintaining a healthy body composition is important for overall health.

While many factors contribute to someone’s overall health, these 5 components of physical fitness are frequently utilized to understand general health-related fitness.

Benefits Of Understanding The 5 Components Of Physical Fitness

We live in a world where fitness goals are often dictated by a singular focus. For example, “I want to lose weight” or “I want to get strong” are common themes in approaching fitness. And while these can help motivate and inspire, they create the potential to lose sight of the big picture of physical fitness.

Whether you are an everyday fitness goer or dream of improved athletic performance, the 5 components of physical fitness can help us consider the big picture of physical fitness.

In the short term, the 5 components of physical fitness can help improve our quality of life. Cardiovascular endurance, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, and body composition all contribute to our ability to complete everyday tasks and activities. We can do anything from moving heavy objects around the house to feeling better getting out of bed every morning.

In the long term, we can support healthy living and disease control. For example, nothing kills more Americans than heart disease and stroke. More than 877,500 Americans die of heart disease or stroke every year—that’s one-third of all deaths. If we can work in regular physical activity using the 5 components as a guidepost, we can support a reduced risk of disease and other chronic ailments.

Get the Lifetime Fitness

E-Book

Proven strategies to introduce more Lifetime Fitness into your Curriculum. Loaded with free lessons, you won’t want to miss this resource!

A Closer Look At Each Of the 5 Components of Fitness

Incorporating various exercises and activities that target these components within a fitness routine promotes overall physical fitness and reduces the risk of various health issues. A well-rounded approach that includes cardiovascular exercise, strength training, flexibility work, and attention to body composition is crucial in reaping the full benefits of physical fitness.

Achieving a well-rounded program that addresses the 5 components of fitness is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, individuals can tailor their regular physical activity plan to their interests, experiences, goals, and more. But to do so, let’s take a closer look at each of the 5 components of fitness, what is happening in our body, and some examples of different types of exercises and workouts that tap into these different components.

1) Cardiovascular Endurance

Cardiovascular endurance involves the ability of the heart and lungs to deliver oxygen to working muscles during sustained physical activity. Both aerobic (with oxygen) and anaerobic (without oxygen) exercises contribute to cardiovascular fitness. Here are examples of both types:

Understanding the aerobic and anaerobic systems can help us better understand the cardiovascular system.

Aerobic Capacity

Otherwise known as “stamina” or “endurance,” aerobic capacity simply refers to your ability to work continuously at a moderate to low effort for extended periods of time without fatiguing or needing to stop.

If you only need a moderate amount of energy, your body uses a slower process to create energy called aerobic respiration. If trained and improved through aerobic exercise, this process can last a LOT longer.

More specifically, your aerobic capacity marks your body’s ability to move oxygen and nutrients to working muscles while also removing metabolic waste.

During moderate to low-intensity exercise, your muscles rely on energy supplied from a combination of oxygen you breathe in, carbohydrates (from the food you’ve eaten recently), and fats (from the energy you’ve stored). This means that improving your aerobic capacity doesn’t only improve your “cardio” conditioning.

Enhancing aerobic capacity can improve blood, oxygen, and nutrient flow to working muscles between sets of resistance training or sprint work. Improving blood flood may also help improve flexibility and mobility. Good aerobic capacity has also been shown to reduce the risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, obesity, diabetes, metabolic disease, and some forms of cancer.

Examples of aerobic exercise include running/jogging, biking, swimming, jumping rope, and even dancing.

Anaerobic Capacity

Essentially, when short, intense bouts of activity are required (a full-speed sprint, lifting something heavy, or going all out in the last 2 minutes of an athletic competition, etc), your body cannot rely on oxygen as a source of energy creation. It takes too long and cannot keep up with the high demand. That’s when the anaerobic energy systems kick in.

There are 2 different systems that can create energy in the absence of oxygen (anaerobically): the Phosphocreatine System and the Glycolytic System.

Phosphocreatine System

The PC system provides an immediate and immense amount of energy very quickly. It’s most useful in something like a 100m sprint race or powerlifting a heavy load for a few reps. The downside lies in its duration. The PC system can only sustain its level of production for anywhere between 8-15 seconds at once. At that point, it simply runs out. It can, however, recharge rather quickly given rest or aerobic recovery (quicker in well-trained individuals).

Glycolytic System

The GC system is the pathway that provides the energy for near all-out activity that lasts anywhere between 30 seconds and a couple of minutes. It’s most useful for some, like a 400m sprint or circuit training.

The downside to the GC system is that it’s process for creating energy without oxygen results in the creation of a couple tricky byproducts – acid (hydrogen ions) and lactate. Many people misunderstand the role of lactate, or “lactic acid.” We often hear people throw around the idea that lactic acid is to blame for your fatigue or soreness after a workout. This isn’t true.

It is the excessive rise in acidity that will eventually shut your muscles down (soreness is a whole other animal we will talk about another time). The acidity interferes with the muscle’s ability to contract and is the reason they feel dead, like “jelly”, or even on fire. At some point, you have to stop.

Putting It Together

Aerobic respiration can eat up this acidity, using oxygen to effectively clear all of the waste products created during anaerobic respiration. But, when your aerobic system can’t keep up (like during high-intensity efforts), your body attempts to slow the rise of acidity by combining that hydrogen ion with another molecule to create Lactate. Lactate can actually then be converted into further energy in aerobic or anaerobic respiration. But, the buildup of lactate also signals the rising level of acidity within the muscle.

The better your body is at preventing this acid build-up, the longer you can go. So, if your aerobic system is in top-notch shape, and you’ve trained at high intensity, you can prevent the build-up of acidity a bit longer than someone else.

At some point, though, the rate of acid production overtakes the clearance of waste and you have to stop. This is your anaerobic or lactate “threshold”.

2) Muscular Strength

Technically speaking, “Strength” is a measure of force production.

Often, people classify this capability through a very narrow lens. Muscular strength is sometimes limited to the ability of a muscle or muscle group to exert maximal force against resistance. Strength is expressed by slower, controlled movements. For example, a heavy squat performed at a slow speed for a single repetition.

And strength can certainly be measured based on the amount of weight lifted for a single rep. This is referred to as a one-rep max, or 1RM. At PLT4M, we include this measure of strength when utilizing our weight training movements like the back squat, bench press, and deadlift.

BUT – the application and measure of strength is not reserved for weight training alone. At PLT4M, we like to think of strength as your muscles’ ability to apply force into/against the physical world. Barbells and dumbbells are great, but before we get there, we employ a host of bodyweight exercises that engage muscles throughout your entire body in strict form.

Moving one’s body against their own body, or gravity, while maintaining proper posture is a display of strength, and strength endurance all it’s own.

3) Muscular Endurance

While separated within the 5 components of physical fitness, there is a lot of overlap to muscular strength and muscular endurance.

Muscular endurance is the ability of a muscle or muscle group to exert sub-maximal force against resistance for an extended period of time. Measurement of this muscular endurance is based on the number of repetitions performed in a given time period or before fatigue shuts us down.

If we improve maximal strength, endurance improves as well. Thus we can assess our ability to perform repetitions of bodyweight movements to track our relative strength overtime, before ever think about a barbell or heavy weights.

Specifically, with the push up and pull up tests, we are assessing the muscular strength and endurance of the upper body. With squats, we can do the same thing for the lower body.

In practical life, muscular endurance is crucial for daily activities that involve repetitive movements, such as carrying groceries, climbing stairs, or performing household chores. Improved muscular endurance makes these activities easier and reduces the risk of fatigue and injury.

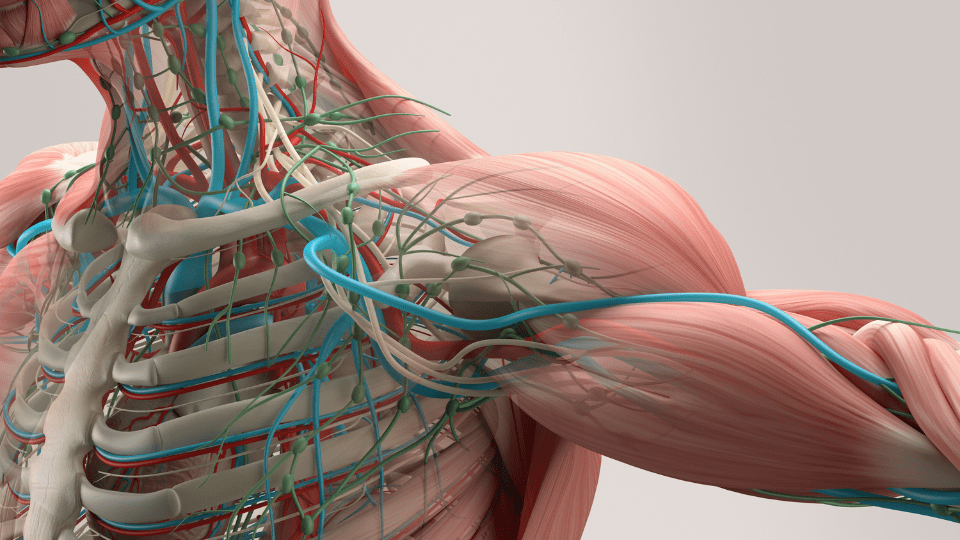

4) Flexibility

To better understand the importance of flexibility as one of the 5 components of physical fitness, let’s unpack both flexibility and mobility.

Mobility is best defined as the ability to voluntarily move a limb or joint through its entire functional range of motion with complete control.

Flexibility, though, is actually just the ability of a muscle to temporarily stretch beyond its resting state, when needed. Even more specifically, it is your muscles’ ability to tolerate being stretched, neurologically speaking.

Basically, if you improve your flexibility through, say, static stretching, your body can move through more extreme ranges of motion without pain. This is but one component of the complete mobility puzzle.

Instead, mobility is a dynamic expression of one’s ability to combine flexibility, with strength, and total neuromuscular control in order to move specific joints through complete, intentional movement patterns.

Combined, if we improve mobility and flexibility, we are more likely to avoid injury, chronic pain, and other nagging ailments that can interrupt daily life. Examples of flexibility training include stretching, yoga, pilates, and even just incorporating it into other workouts and training programs.

5) Body Composition

Body composition refers to the relative proportions of fat and non-fat mass in the body. It goes beyond just measuring body weight, considering the distribution of muscle, bone, organs, and body fat. In essence, it provides a more comprehensive understanding of an individual’s physical makeup.

Typically, when people talk about body composition, they jump right to body fat composition and think that they need to measure and track total body fat percentage. Another step further, individuals will look at body mass index (BMI) as a way to measure and monitor overall health. However, for the purposes of long-term healthy living, we shouldn’t be as consumed about body fat alone, as much as all the different parts that make up the human body.

Taking a look at the complete picture can help us to understand of all the different parts of our body and how we can best support our overall health.

Our Body Consists Of:

Bones: The human body is supported by a remarkable framework of bones, totaling 206 in adults. These bones provide structure, protect vital organs, and serve as attachment points for muscles, allowing for movement.

Muscles: Comprising nearly 40% of body weight, muscles are essential for movement, posture, and overall functionality. There are over 600 muscles in the human body, ranging from small, intricate muscles to larger, more powerful ones.

Adipose Tissue (Fat): While fat is considered in the context of body composition, it’s worth emphasizing that not all fat is detrimental. Essential fat is necessary for normal physiological function, including hormone production and insulation.

Tendons: Tendons are connective tissues that attach muscles to bones, enabling the transfer of force and facilitating movement. These fibrous structures play a crucial role in the biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system.

Ligaments: Similar to tendons, ligaments are connective tissues, but they connect bones to other bones, providing stability to joints. Ligaments play a vital role in preventing excessive movement and maintaining the integrity of the skeletal structure.

And Wait…There Is More!

Organs: Organs are specialized structures with specific functions, such as the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and digestive organs. They play vital roles in maintaining bodily functions, and their composition contributes to overall body mass.

Fluids: The human body is composed of a significant amount of water, which is distributed within cells, blood, and other bodily fluids. Proper hydration is essential for maintaining optimal health and influences body composition measurements.

Connective Tissues: Beyond tendons and ligaments, there are various connective tissues, including fascia, cartilage, and the extracellular matrix, that contribute to the body’s structural integrity.

Blood: Blood is a fluid connective tissue that transports oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and waste products throughout the body. While blood is not typically included in discussions of body composition, its volume contributes to overall body weight.

Skin: The skin is the body’s largest organ and plays a crucial role in protecting internal structures.

Key Takeaways On The 5 Components Of Fitness

Altogether, the 5 components of fitness help to create a picture of overall health and wellness. Overall, having a balanced and well-rounded approach to physical fitness can support our bodies in the short and long term.

For some, this might mean more strength training and less aerobic fitness. And for others, it might mean more flexibility and muscle endurance workouts. But we shouldn’t completely ignore one of the fitness components completely, as they all are interconnected in our lives.

Again, we cannot over-emphasize that the 5 components of fitness don’t inherently dictate and prescribe a specific training plan and workout regime. Each individual can take and mold the information from above and find a regular physical activity schedule that supports and enhances our daily activities and lives.