[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

How to Teach & Perfect the Deadlift

Teaching the Deadlift

For good reason, the Deadlift is beloved by coaches everywhere. It is an excellent way to develop pure, total body strength as well as reinforce good posture and proper mechanics that relate to many other movements. Unfortunately, though, it is also a movement where strength can trump form – it’s too easy to do it the wrong way. You can execute a heavy rep with egregiously poor technique, and we see this far too often with high school athletes who want to move big weight. The result can range from inefficiency to a legitimate risk of injury. While the deadlift appears to be a relatively simple lift, proper execution often proves far more difficult. Here, we identify just a few of the major coaching points that we use when teaching the lift to any of our athletes. We are constantly looking to perfect technique in order to maximize gains, while simultaneously minimizing risk.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/s1e9PtrvIjA”][vc_column_text]Athletes should begin by getting into a hip-width stance with the feet under the barbell such that it “cuts the shoes in half”, or sits right over the middle of the shoe laces. Then, we like to instruct athletes to place the palms on the thighs. From here, we perform a simple good morning, letting the hands slide down the leg until they reach the knee cap. Hands then move to thumb-swiping distance outside of the legs. Now we have the athlete settle the hips and shoulders down together, maintaining the nice, flat back, until the hands can grasp the bar. Notice that the knees have not driven excessively forward over the bar, the hips and shoulders have kept the same relative angle between them, and the eyes are down. We then instruct our athletes to “push the floor away”. This brings the bar up to the knee without changing the angle of the back. We want to keep a nice tight core throughout. At the knee, we open the hip and reverse the hinge of the good morning movement from earlier. We open only to full extension and no further. We do not want any excessive leaning back at the top. To return the bar, we repeat the good morning, pushing the hips back as the torso inclines forward. The knees have not bent yet, and the hips stay high. At the knee, we again settle the hips and shoulders and the same pace until the bar is back on the ground. The deadlift is a surprisingly complex lift, and we take great lengths to feature many different coaching points, tips, and drills on the movement. Be sure to check them all out!Fix Your Deadlift

The Set Up

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bYopFmhWS_A”][vc_column_text]Often, athletes have failed the lift before they’ve even begun. Improper set up for the deadlift can result in a host of technical errors during execution. One of the most common issues we see is incorrect hip and shoulder positioning. Some athletes set up with super low hip level, much like a squat – others do the opposite, treating it more like an RDL. We want to find the middle ground. With the bar just in front of vertical shins, the athlete’s hips should be above the knee (from a profile view), the shoulders above the hips (and in front of the bar) and gaze at a downward angle (neck in a neutral alignment – no “eyes to the sky” here!). Correct alignment will help ensure athletes’ maintain proper back position and allow them to generate the most force into the ground.Pull vs. Push

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kCSddVyuWJc”][vc_column_text]While the deadlift is most often referred to as a pulling movement, we actually prefer to associate it with a “push” when teaching new athletes. Hearing “Pull” often leads to movement deficits – hip & shoulder disassociation during the initial ascent phase, loss of lumbar curve, etc. To combat these issues, we instead tell the athlete to focus on pushing the ground away with their legs. This helps to keep the hips and shoulders rising at the same time with a tight core.Losing Lumbar Curve

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E84nYBGRAFw”][vc_column_text]The deadlift is an integral part of any fitness program, and a movement all trainees shoulder learn. From hip hinge mechanics to posterior chain strength and mobility, the deadlift offers a host of health and performance benefits. Unfortunately, though, it is also a movement done wrong more often that right. It’s an exercise in which strength can trump form – aka it’s too easy to complete a rep with improper technique, which leads to serious risk of injury (most often related to the lower back). This does not mean we should avoid the deadlift. It simply means we must pay extra attention to proper execution, and always keep weight as a secondary priority. One of the most frequent issues we see is the loss of lumbar curve (aka a flat back) by athletes pulling more weight than is appropriate. We must hold ourselves, and those around us, accountable to proper form when attempting to pull big weight. We must maintain a stable core and keep from allowing the low back to round up during the drive away from the floor. If we see any flexion of the lower back during a rep, it is a sure sign that the weight is too heavy in relation to our mechanics. We must lower the loading and reinforce great movement before adding heavier weights back into the equation.The Return

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XJ0DkzkEP2g”][vc_column_text]Even athletes with impeccable deadlift form off of the floor often have a tough time with the eccentric portion of the deadlift, or the “return”. When working consecutive reps within a given set, this half of the movement becomes vital to proper execution. Essentially we want to mirror the concentric half of the lift in reverse. The athlete should push the hips back and “look out over the cliff” until the bar reaches the knee. Only then should the athlete re-bend the knee. Early knee bend is a fault we see frequently, and leads to both inefficiency moving weight and potential injury.Deadlift Drill

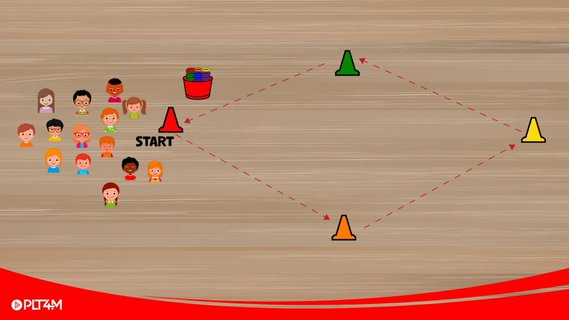

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Ml7Li2cCTI&t=40s”][vc_column_text]At PLT4M, we’re total sticklers for proper deadlift form. We love the lift as a tool for developing raw strength as well as a rigorous reinforcement of core stability, posterior chain mobility, and spinal alignment and posture . Too often, though, we see young athletes pulling heavy loads off of the ground with sub-par technique or worse. Not only are they sacrificing maximum potential force production with inefficient movement, they are putting themselves at the very real risk of legitimate injury. In order to combat this risk, we like to spend time drilling our “pulling” technique anytime we get the chance. Here we have a complete drill for athletes to correct or improve their positions while warming up for heavier loading. With a PVC pipe or empty barbell, perform 5 slow reps of each of the following:- Top-Half Deads (Like an RDL, from hip crease to the knee). Focus on pushing the hips back, keeping the bar on the quads, knees remain where they are, lumbar curve maintained.

- Bottom-Half Deads (mid-shin or ground to the knee). Focus on pushing the floor away, instead of pulling the bar off the ground. Hips and shoulders should rise together, maintaining a good flat back.

- Pausing Deads. Combine the two movements, with a deliberate pause at the knee.

- Full Deadlifts. Blend both pieces into one fluid movement. Focus on returning the bar the exact same way you pick it up.