Accountability can be considered the Holy Grail amongst coaches. What is it? How do you develop it? Is it actually important? Let’s take a look…

Any coach, of any sport, wants to win. That should be a fairly agreeable assertion. So, if we all want to win, what separates those who do, from those who don’t?

Is it the talent on the roster? Is it the attitude of the athletes? Is it coaching?

There is of course no simple answer just as there is no simple formula for winning. If there was, everyone would follow it.

However, there is one thing that is a prerequisite for success – Accountability.

You can have the most talented roster. You can be the better X’s and O’s coach. But, if your program lacks accountability, the chances of consistently winning are greatly minimized – if not impossible.

So, let’s dive in and understand what Accountability truly is, and how to grow a culture of accountability within any program.

Definition of Accountability

When it comes to definitions, Webster’s Dictionary is always a good starting point. Webster’s defines accountability as:

“Accountability is defined as an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility for one’s actions”.

Webster's Dictionary Tweet

Straightforward enough. Accountability, according to Webster, is the willingness to take ownership of our actions.

Looking to the field of psychology, we can find a slightly different definition, and one that applies even more specifically to the athlete-coach relationship:

“Accountability is the condition of having to answer, explain, or justify one’s actions of beliefs to another”.

This definition frames accountability in a more relational setting. How do we, as individuals, answer for our actions? How do we justify them to someone else – likely someone who holds some responsibility for us, such as a parent, teacher, or coach.

7 Keys to Build a Culture of Accountability

A culture of Accountability is a precursor to success, regardless of sport. Download the Accountability E-Book and start put these 7 tried and true principles to work today!

History of Accountability

The concept that we are responsible for our actions is actually a matter of some debate. Philosophers and psychologists have long argued over the concepts of “determinism” and “free will”.

Determinism suggests that people act based on cause-and-effect relationships and therefore could not have acted any differently in any given situation.

While proponents of free will admit that genetics and environment influence decision making, they maintain that decision making remains within the power of the individual.

While our reactions to events (the cause-and-effect) can sometimes feel automated and many times is, it is built on past experiences, on past choices, and consequently, on habit.

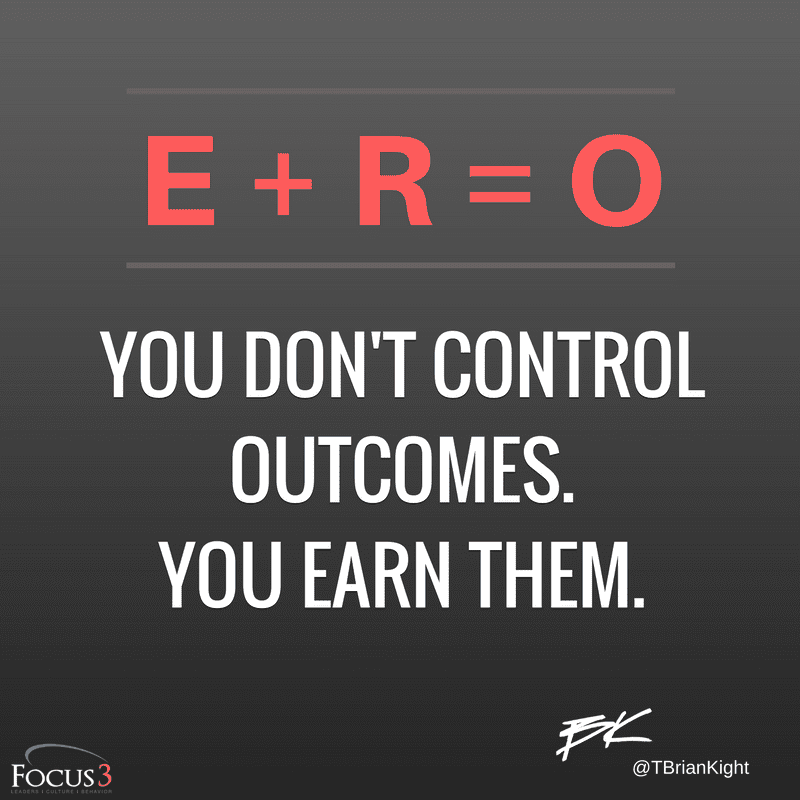

Brian Kight, an expert on leadership and culture who has worked with many of the nation’s top sports programs including Ohio State’s football program, coined the term “E+R=O”. Spelled out, it means:

Events + Responses = Outcomes

The thesis? Outcomes you experience are the result of how you respond (and have responded) to events in your life.

According to the free will school of thought, these responses are within your control. And as abundant research on habit building has shown, repetition matters.

If we spend our life making excuses and shirking from responsibility, then our pre-programmed response to any negative event will be to avoid accountability.

The determinist views this reaction as inevitable. We believe it is a product of culture and upbringing.

Enough history though. Let’s dive in and look at 7 key principles to build accountability in your program.

1. Accountability Depends on Clear Expectations

When it comes to accountability, this is almost universally the number one principle. Do a quick Google of “accountability”, and any article or website you click will inevitably start here.

Why? Because it is the number one principle – the cornerstone – of establishing a culture of accountability.

Unclear expectations create accountability gaps.

“I want you to put in a lot of work this off-season”.

“You need to commit to the weight room”.

These are examples of what not to do. These are unclear, undefined expectations. The only way to assess them is subjectively, and chances are your interpretation varies greatly from that of your athletes.

What are examples of clear expectations?

“Our Spring Off-Season Weight Program starts Jan. 1 and ends March 31.”

“In-Season Athletes are expected to lift 2x a week, Off-Season kids 3x a week.”

These are objective, clear, expectations.

Other areas, specific to your weight room culture, where you can set expectations and hold athletes accountable are:

- Dress Code – Don’t allow any deviation from the set dress code

- Clean Up protocol – Where do things go and what should the room like like at the end of a workout

- Language and Music – are there any limitations or expectations around what can be said/played

When Should Expectations be Set?

Immediately. Expectations must be known from Day 1.

Why? Studies in psychology show that the effects of accountability vary depending on when a person is informed that he or she will be evaluated.

If informed beforehand, people will expend more energy trying to adhere to expectations. If informed after however, they will stick with their original decisions, and try to justify their actions.

Get Your Accountability E-Book

A culture of Accountability is a precursor to success, regardless of sport. Download the Accountability E-Book and start put these 7 tried and true principles to work today!

2. To Hold Others Accountable, Lead by Example

While this seems straightforward and easy, it is often one of the main culprits when it comes to a lack of accountability.

As a coach, you must lead from the front.

Want kids to be on time to film? You better be there first.

Want kids to commit to your summer weight program? You cannot offload your duties on Captains or the kids themselves.

Having an app or technology that tracks kids participation won’t matter if you yourself, or at least some of your staff, are not present in the weight room.

The question to always ask yourself is:

“If I am not willing to do it myself, how can I expect my athletes to do it”.

Looking to take Fridays off in the Summer? Better not schedule workouts on that day.

Don’t want to wake up early? Better not schedule early morning workouts.

Jocko Willnik, a retired Navy Seal who served in the Iraq War as the commander of Seal Team 3’s Task Unit Bruiser, wrote the book Extreme Ownership after his military career.

The general thesis is that if those under your responsibility fail, it is your fault. No ifs, ands, or buts about it.

His second chapter, titled, “No bad teams, just bad leaders…” drives home the importance of leading from the front.

It can be easy to blame a lack of culture or a lack of on-field success on the athletes.

“This team lacked leadership,” is a common response to a bad season. I know. I’ve said it myself.

But, while that may be true, the buck stops with you. What did you do (or not do) to produce a lack of leaders?

These are hard questions that require a LOT of self-awareness and humility. But we must be able to ask and answer them.

3. Empower Participants to Boost Accountability

Ok, so far, we laid out the need for clear expectations. We covered the need to lead from the front as the coach.

With these two principles in place, we must now ensure that our athletes are empowered to meet the expectations – whether they do or not is up to them.

What does this look like? Well, let’s examine it through the lens of the off-season, starting with weight room availability.

Do you offer weight room times that are amenable to your kids schedules? Opening the weight room for one hour after school may not be enough if you have kids who need extra academic support after school, or if they have to work a job after school.

Making the commitment to early morning lifts, despite this being less ideal for you, may be necessary to empower your kids with the ability to attend lifts.

To use another example from our first principle, if we are going to set a dress code for the weight room, are we giving them what they need to meet that code?

Requiring blue team shorts and grey team shirts is unfair if kids only have one or two pairs. Getting on kids for not wearing the correct gear to a workout when they haven’t been given enough attire to meet the expectation is unfair and is likely to engender resentment rather than accountability.

4. Accountability is Impossible without Objective Measurement

Setting expectations is the first step toward a culture of accountability. However, without the ability to measure performance against those expectations, what’s the point?

Establishing that kids must attend 30 workouts for a total of 30 hours over 3 months is all well and good, but if kids know that you are not tracking their progress toward the desired outcomes, they are more likely to skip workouts.

Measurements must be objective. Iron-clad. You either showed up this many times or you did not.

Subjectively recognizing kids who you think were there a lot, or who you recall showing up, is a sure way to undermine your credibility and the culture you are trying to build.

So whether it is an attendance spreadsheet, a “demerits” log, or a training app, be sure that you have a system in place to measure performance against the pre-established expectations.

5. Transparent Feedback Strengthens Accountability

On-going feedback is a critical element of establishing a culture of accountability.

Part of the reason we set clear expectations up front is so we can vigilantly measure them and provide kids with feedback throughout the process.

If a Freshman shows up every day for the first two weeks, giving him affirmation of his effort can go a long way.

Conversely, if an athlete begins to slip, addressing it immediately is critically important.

Otherwise, it becomes a habit that calcifies and becomes harder to break.

What Does Open Feedback Look Like?

Feedback should be a two way street. You must inform your athletes of how they are doing, correcting errors, and recognizing success (more on this in Principle 7).

However, athletes must be empowered (there’s that word again) to provide you and your staff with feedback.

A great way to do this is a “Captain’s Council”. In addition to your team captains, select 3 kids from each grade.

Meet with them at a set time every week, and solicit feedback from the group on how the team is doing.

Are the expectations laid out reasonable? Is weight room availability sufficient? Are there kids on the team going through something unknown to you that may require an altered approach?

This type of communication system makes the athletes feel heard, and also ensures that everyone from staff to athlete is on the same page.

6. Define Consequences for a Lack of Accountability

At the high school level, this can be extremely difficult. Unlike the college ranks, your team may lack depth. Additionally, there may be rules outside of your control on making cuts or administering “punishments” .

Regardless of the constraints, we must find a way to establish consequences for actions that are clear and known.

These can be as simple as saying that kids who attend over 90% of workouts do not have to participate in the dreaded conditioning test at the start of camp.

The responsibility of bringing the balls and equipment to practice, often reserved for the underclassmen, can become the responsibility of those who didn’t participate in off-season workouts.

The consequences don’t need to be draconian. They just need to be defined and implemented.

If an athlete A participated in every workout and Athlete B never did, what is the likelihood that Athlete A will continue to put in the same effort?

Unless they possess a great deal of intrinsic motivation, the chances are slim.

7. Reward Desired Behavior to Increase Accountability

Let’s be honest, we’re dealing with high school kids. Not every kid on your team is looking to play at the next level. This means that their “intrinsic motivation” may be lacking. And that is okay.

We can improve motivation by recognizing and rewarding desired behavior.

Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation and Their Role in Accountability

According to the theory of Self-Determination, there are two sources of motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic.

Extrinsic motivation refers to behavior that is driven by external rewards. These can be tangible rewards like T-shirts, badges, or trophies, or they can be intangible, like praise and recognition.

Intrinsic motivation on the other hand is driven from within. It is based on actions naturally satisfying to the individual, like the love of the sport.

Claim Your E-Book!

A culture of Accountability is a precursor to success, regardless of sport. Download the Accountability E-Book and start put these 7 tried and true principles to work today!

There are subclasses to these types of motivation, but we will save you the physcology lesson.

Suffice it to say that most kids’ motivation for participation in sports will derive from a mixture of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. And if my experience after a decade of coaching is any indication, more kids will be extrinsically motivated – and that’s fine.

Gamify the Weight Room to Motivate Athletes

We can use this to our advantage through a system of rewards – gamification of the off-season.

One example from Loyola Academy, a perennial Top 25 football program north of Chicago, uses different color T-shirts that kids earn based on their off-season performance.

This not only recognizes kids who are meeting expectations, but it gives kids lower on the totem pole something to aspire too. You can easily mimic this by associating T-Shirt colors with days present or hours of workouts accumulated.

At one of my coaching stops, we created a point system for different actions in the off-season, with things like points for winning a finisher or hitting a workset, and subtracting points for tardiness, misses or other infractions.

Drawing from the Military’s system of ranks, kids started as “Privates”. As kids climbed in points, they were given a promotion of rank which was accompanied by a rubber wristband, T-shirt or other prize. The higher the rank, the better the prize.

Ranks and points were displayed on a big leaderboard outside the football office, providing a form of transparent feedback throughout the off-season.

This helped clarify for everyone who our leaders were in the weight room.

Whatever system or approach you choose, you must make sure that a system of recognition is in place. Additionally, this recognition should be done in front of their peers.

We all love recognition – kids more than anyone. Lean into that.

Practical Guidelines for Building Accountability on Your Team

Defining the principles of accountability is relatively simple. Many of the items above likely struck you as common sense.

As with your weekly gameplans, what matters is not just the plan, but the ability to execute the plan.

The Navy Seals have a great saying, which I will paraphrase:

“An average plan performed perfectly is better than a perfect plan performed averagely.”

So what can we take away from this when it comes to putting a plan for accountability into practical use?

Keep it Simple

The more complex you make your expectations and systems of measurements, the more work you create for yourself. The last thing you want to do is create a system that you cannot keep up with.

Furthermore, if kids can’t understand it, they won’t buy into it.

Set a clear number of attendances or hours desired.

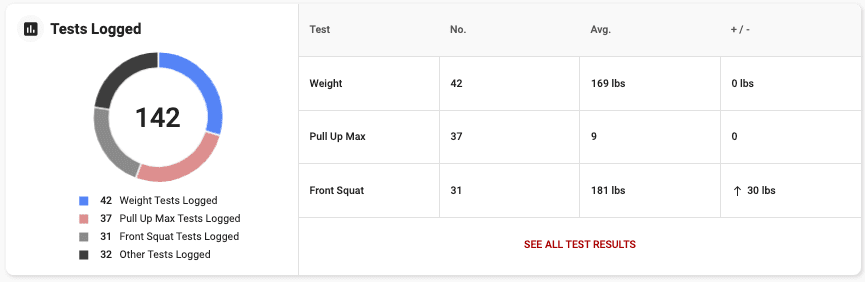

Using a system like PLT4M, you can easily track and tally this information.

Recognize, Reward, Repeat

Don’t forget, these are high school kids. Half their day is spent trying to accumulate likes and shares on TikTok and Instagram.

Rather than trying to radically change that behavior, embrace it and put it to better use.

Recognize kids who are meeting expectations. Reward kids who are setting PRs or seeing great results. Then repeat that every week, every month, every year.

PLT4M’s reporting capabilities allow you to easily see top results from a day’s workout and recognize the top performers instantly.

Additionally, Report Cards can be generated for any time frame, allowing you to hand kids a physical report card that shows their progress in key assessments, and their participation states like Attendance and Time spent training, compared to their teammates.

Conclusion

Building a culture is hard. Maintaining it is equally difficult. The moment you let up or stop setting expectations is the moment that the kids begin to slip through the “accountability gaps”.

While an online system like PLT4M is in no way required to build and maintain a culture of accountability, it can certainly help.

By now, technology should be widely accepted as a source of efficiency. Be it Google Sheets, PLT4M, or another tech service, don’t make your life harder than it needs to be.

Set clear, finite number expectations.

Figure out how you will measure performance against expectations.

Communicate openly and consistently with your athletes.

Make consequences and rewards known, and act on them.

References

https://www.gallup.com/workplace/257945/ways-create-company-culture-accountability.asp

https://www.trainingpeaks.com/blog/what-motivates-successful-athletes/

https://www.trainingpeaks.com/blog/what-motivates-successful-athletes/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/how-we-work/201601/the-right-way-hold-people-accountable

https://www.range.co/blog/accountability-in-the-workplace

https://www.amazon.com/Extreme-Ownership-U-S-Navy-SEALs/dp/1250067057